Research highlight

Focusing light with invisible patterns

Replacing a bulky traditional lens system by an ultrathin, planar optical device: that is the promise of so called metalenses. In a project funded by the top sector High Tech Systems and Materials, Francesca Cussiol, Jo de Wit and Sushil Kumar are investigating the possibilities of this new class of optics.

Flat lenses

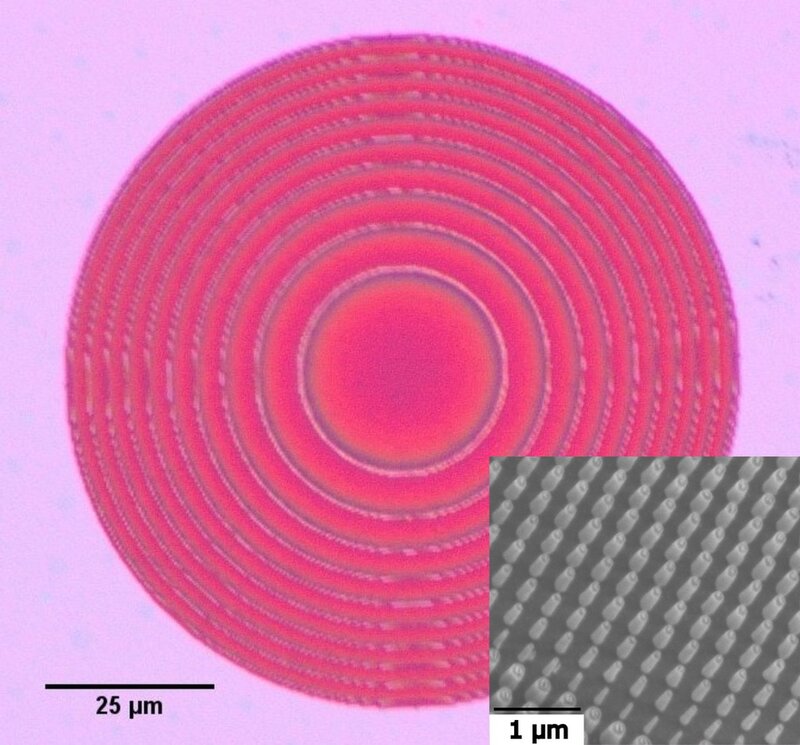

By carefully constructing nanoscale structures with varying sizes and shapes on top of a flat dielectric surface, it is possible to bend and focus incident light. In recent years, these so called metalenses have gained significant attention, since nanofabrication has matured enough to produce the nanoscale pillars of material that can manipulate light at will.

Cussiol, De Wit and Kumar are studying the possibilities of using metalenses for chromatic correction. ‘We explore metalenses as the future of aberration correction,’ De Wit, who is seconded from ASML to TU/e for two days a week, summarizes the aim of the project. ‘More specifically, we want to find an achromatic metalens that has the same focal lengths for a wide variety of wavelengths.’

Fundamental (im)possibilities

When the researchers started their quest, they discovered to their surprise that there was not a lot of literature about the fundamental possibilities of metalenses.

Together with PhD researcher Francesca Cussiol, De Wit found that the physics that describes the wavelength dependence of a single layer metalens predicts that achromatism is either very difficult or perhaps even never to be achieved.

‘We have identified three effects that

that play a role,’ Cussiol and De Wit explain. The primary effect arises from the nature of the metalens as a diffractive structure, where the focal length is inversely proportional to the wavelength of the incident light. The second effect is diffraction at the lens aperture. Where both diffraction effects lead to shorter focal lengths at longer wavelengths, the third effect, being the dispersion of the metalens material, has the exact opposite result. ‘Unfortunately, the dispersion effect is too weak to counteract the other two,’ De Wit comments. That is why, in their publication in Applied Optics on the subject, the researchers concluded that – at least for single layer metalenses – truly achromatic performance is only feasible for very small metalenses that have a sharp, clean focus and long focal length.

Speeding up simulations

In order to design the patterning for a metalens in such a way that the light is manipulated according to the requirements, simulations are used. PhD researcher Sushil Kumar is working on this computational side of the HTSM funded project. ‘I’m working on a method that can simulate an entire metalens made up of millions of tiny pillars. At first, our goal was to create an achromatic lens that could focus light across a broad range of wavelengths, from the visible to the near-infrared, onto a single focal point. But after my colleagues concluded that such a design is probably impossible, we decided to narrow our focus to developing an achromatic lens specifically for visible light.’

While the majority of groups in this field of research is focusing on simulating the spectral result from a single pillar contribution, Kumar is developing a solver that calculates the collective behavior from all of the pillars. ‘Because it’s nearly impossible to fabricate pillars that are perfectly identical, simulations assuming uniform structures fail to

accurately reflect real-world conditions. To address this, we are developing a simulation solver that accounts for the interactions between individual pillars. Beginning with a defined geometry, the goal is to model how light behaves across the entire metalens, providing a more realistic prediction of the overall light field.’

Since that is a very computation-intensive operation, Kumar searched for an alternative solver. During the first year of his PhD project he already managed to come up with an alternative that is ten times faster in calculating how the light scatters off a matrix of multiple pillars.

Contribute to new field

Kumar is intrigued by the promise of metalenses. ‘I find it fascinating that a thin layer of structure can manipulate and control the light on a macroscale. To put in perspective: we are talking about lenses that are invisible to the naked eye, with a thickness that is 100 times smaller than the thickness of a human hair. The field of metaoptics is growing and penetrating the market in a wide variety of applications. It is very rewarding to be able to contribute to this field and be part of its maturation.’

PhD candidate Cussiol is now looking into the possibilities of fabricating a wide field of view metalens that corrects for spherical aberration and coma (a lens aberration that causes off-axis points to blur into a comet-like shape, ed) to focus light coming in at different incidence angles. ‘Though the actual fabrication of metalenses is hard, it is nice to be a part of this exciting development.’